|

Interesting

Reading for 2014

Charles Dickens -

The Pickwick Papers (1836)

|

|

The Posthumous

Papers of the Pickwick Club was the fictional

publication that really made the name of Charles Dickens famous.

After his reasonable success with descriptions and written

sketches of London life (Sketches by Boz) in 1833-36, Dickens

gained a popular following and the beginnings of a loyal

audience thanks to the increasing success of

The Pickwick Papers.

His publishers commissioned Dickens to

provide the text for a picture novel about unsuccessful,

bumbling sportsmen, with the pictures supplied by Robert

Seymour. But rather than wait to be given illustrations to

describe, Dickens began writing his descriptions before anything

had been drawn and so, increasingly through

The Pickwick Papers, his words

took precedence over the illustrations. Seymour, who had

originally proposed the idea of a series of illustrations of

city-dwellers inexpertly hunting etc., shot himself before the

second installment's publication – though that probably wasn't

just due to Dickens's increasing level of artistic control. |

The collection of illustrations and story-captions

detailing the exploits of the Pickwick Club eventually attracted a wide

readership, and it's easy to see why. While not quite the soap opera of its day,

The Pickwick Papers is a running light

comedy, with each installment dropping its increasingly familiar (dare I say

predictable?) characters into fresh situations full of potential mishaps and

fumbles.

Bill Ehlig and Ruby Payne

What Every Church Member Should Know about Poverty (1999)

|

|

Churches often are perceived as open,

welcoming environments. Many times, that's what they are. But

congregations, without even realizing it, sometimes make

themselves inhospitable to impoverished people.

Many of us in the church genuinely want to

be available to those in their communities who are experiencing

poverty. However, churches are often operated with a

middle-class mentality. This middle-class mode of thought makes

it difficult for those from poverty to assimilate into the

congregation. In What Every Church

Member Should Know about Poverty, Payne, a national

expert on poverty, and Ehlig, an ordained minister, use stories

to help illustrate the way people from poverty view middle-class

churches. They then provide solutions and tactics to teach

church members and leaders some of the special considerations

that can be afforded the disadvantaged. One recommendation, for

example, is that congregations reach out to the poverty-stricken

in a way that shows mutual respect and not a sense of charity. |

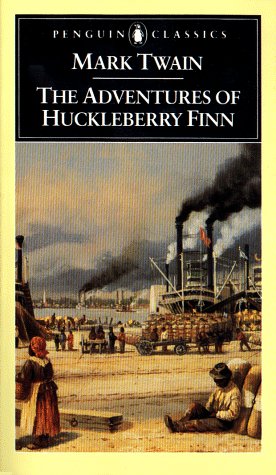

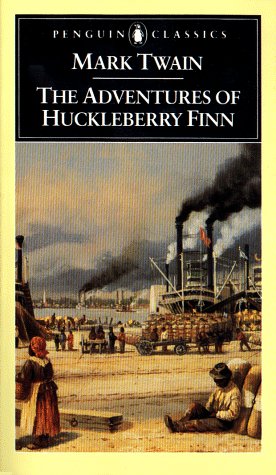

Mark Twain - The Adventures of

Huckleberry Finn (1884)

|

|

There's a reason

why many consider The Adventures of

Huckleberry Finn to be one of the great - if not the

greatest - American novel. It broke many of the literary rules

of its time and thus set the pattern for much of American

literature ever since. It's told in first-person dialect by a

great-hearted but ignorant bumpkin of a boy who understands far

less than the reader but who knows how to follow his heart over

his head. And it deals forthrightly, and scathingly, with

racism, the great American problem.

Those who attempt to ban this book (and it

is one of the most frequently challenged, year after year) can't

see the forest for the trees. They see the liberal use of the

"N"-word and assume it's racist, when in fact it's just the

opposite - it's a powerful, and powerfully moving, statement

against racism (as well as slavery, war, and a host of other

American problems). Despite its flawed final section, when Tom

Sawyer reappears and the author reverts to the style of that

lighthearted, lightweight book, this remains, more than 100

years after its publication, a book that every American could

profit from reading. |

Willa Cather - My Ántonia (1918)

|

|

Willa Cather's best-known work,

My Ántonia, is a novel we

often first encounter as young adult literature, a book many of

us actually enjoyed in our youth. We feel comfortable leaving it

safely, fondly stored in our memory banks, rickety as they may

be, where it remains a humane story about a courageous Bohemian

immigrant girl forced by fate and family exigencies to grow up

on the beautiful, harsh flatlands of Nebraska.

We remember Jim Burden, who recounts

Antonia's adventures as well as those of his own rural childhood

with affection. We recall characters like the Russian friends,

Pavel and Peter, with haunted clarity. We feel enduring fondness

for Lena, the dressmaker. We still despise the evil money-lender

Wick Cutter. And scenes such as the one where Jim heroically -

at least to Antonia - bashes the head of a rattlesnake with his

spade remain with us, so startling were they when we first read

them. |

What's interesting about

My Ántonia is how it manages to function as a perfectly

inviting story for young readers, and how an adult willing to revisit it

with a more developed critical eye can appreciate it for the subtly

sophisticated narrative it truly is. In this regard, it's not unlike a

wildly different book, Alice in Wonderland. Great fun for kids,

psychologically captivating for grownups.

There are two things to note about the book: its wonderful

descriptions of the landscape and life on the frontier; and its capturing of the

emotions of the characters. You might say that

Cather captures the interior and exterior landscapes; the physical and emotional

terrain. This allows her to create – or perhaps recreate – a full and believable

world. This is one of the gifts of great literature: it allows us to see how

others might have lived; to imagine the possibilities and contours of life

outside of our own experiences.

|